Good post cuttlefish! Just to highlight some things:

quote: (2) Although in my view it is not yet possible to confidently attribute the salmon decline to one single cause, the concurrent and increasing influences of climate change, global warming, harvest pressures, and aquaculture are almost certain to have profound impacts on British Columbia’s salmon populations and the province at-large.

Unless addressed, both private sector (fisheries, aquaculture) and public sector costs will increase substantially as public policy decisions are made that are both ineffective and possibly harmful—and we may completely lose the salmon resources that are supposedly an integral part of the fabric of this province. Lest this final statement sound too extreme, then we need only look at the devastation wrought in just 20 years by the declining marine survival of salmon and the loss of most of the commercial salmon fishery in British Columbia, and along with it close to 20,000 jobs. As we are no farther ahead now than 20 years ago in understanding what the problem is and thus how to deal with it, it seems entirely plausible that in another 20 years marine survival will be only 1/10th the current level—0.1%. Should this prediction seem outlandish, one need only look at Sakinaw Lake sockeye, which now has an average marine survival rate of only 0.2% (see below)—1/5th the level precipitating the 2009

Fraser River calamity and the reason for the Cohen Commission.

7. The relevance of the hypothesized link between fish farming and major mortality (such as occurred for the 2009 adult Fraser River runs) depends upon the degree that the mortality event can be isolated as occurring close to the time the Fraser River sockeye smolts pass through the region containing salmon aquaculture operations; if the mortality was due to disease transfer from fish farms then a reasonable time line for the development of major mortality is that it occurred within 19-32 days after passing the aquaculture sites.

8. We emphasize that neither our own telemetry data nor the synthesis we have outlined in this submission prove a causative link between aquaculture and wild salmon survival because direct evidence is lacking. Claims (i) that the 2009 Fraser River run failure was caused by disease transmission from salmon farms to the Fraser sockeye smolts as they migrated through the area and (ii) that oceanographic changes in Queen Charlotte Sound affected smolt survival are both consistent with the available data as we understand them. However, we believe that our acoustic telemetry data set in the context of other observational data provide an important scientific advance in our understanding, as it places the timing and likely location of the high mortality in the region just after passing the fish farms28. Because Queen Charlotte Sound is also traversed by simultaneously migrating sockeye stocks from the south (Columbia River (Redfish Lake & Okanogan Lake) plus west coast of Vancouver Island stocks) that did not experience the same elevated mortality rates and had excellent survival in 2009, this may tip the balance more in favour of the disease transfer hypothesis - all of the sockeye populations experiencing high adult returns in 2009 are believed to migrate north via the west coast of Vancouver Island in 2007, and there is currently no evidence that they use Discovery Passage as a migratory pathway. Tempering this last point, however, is the basic fact that in the absence of directed telemetry studies on these populations there is no hard evidence to back up the widespread belief that Columbia River sockeye stocks migrate north around Vancouver Island and stay on the outer shelf rather than migrating through the Strait of Georgia.

Our contribution has been to narrow down the likely location for the mortality, but not demonstrate the cause. However, to scientifically prove or reject theories concerning the role of fish farms requires a commitment to experimentally test causation, in this case that exposure to fish farms increases mortality relative to animals not so exposed, and to a level of impact sufficiently large to justify regulatory intervention. From this perspective, the potential impact of aquaculture is similar to many other situations where one economic activity (such as pollution) results in some degree of harm to another. Rigorous experimental designs of this nature require controls and are possible to do, but DFO has failed to take the scientific lead and has instead relied on much more limited observational evidence. (The same comment applies to some—but not all—of the work done by the critics of fish farms).

http://www.cohencommission.ca/en/submissions/ViewASubmission.php?sub=127

Well, can I add to the above? You might want to take the following into consideration, while reading and thinking about the above information? It was brought to my attention that I posted they following, “I do have proof of this information! Proof they culled those smolts. Proof they have and are fighting a long time Kudoa thrysites parasit problem, along with proof there is no cure and no vaccine…” And I did NOT mention the long time problem with “IHN epizootic in farmed Atlantic salmon in British Columbia” and was asked if I had read the following study:

Investigation of the 2001-2003 IHN epizootic in

farmed Atlantic salmon

in British Columbia

Prepared by

Sonja Saksida BSc DVM MSc

Sea to Sky Veterinary Service

Campbell River, British Columbia

http://www.agf.gov.bc.ca/ahc/fish_health/IHNV_report_2003.pdf

Well, I am familiar with IHN, but hadn’t read that study - I have read it NOW – and suggest everyone read it! With or without DFO, Canada, or the Norwegian Atlantic fish farms involved releasing any information, “Houston we have a problem!” At this point, I guess I can only assume the “culling” of those $7 million (NOK) of Atlantic salmon by Marine Harvest in 2007, was probably due to a “SEVERE” outbreak of the disease Infectious hematopoietic necrosis virus (IHNV). Which, was right on and during the 2009 Fraser River Sockeye smolts outmigration, in 2007! The house is smoldering – it might be time to throw some gasoline on it and GET THOSE DISEASE RECORDS RELEASED!!!

To point out a few things here, also! First note this study paid for by Canada and BCSFA… So I certainly hope no one will try telling me, DFO, BCSFA, or any of the NORWEIGIAN fish farms were not aware or don’t have this knowledge!

quote:

I would like to thank the British Columbia Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (BCMAFF) and the British Columbia Salmon Farmers Association (BCSFA) for funding the study. I would also like to thank all the companies (Atlantic salmon producers and suppliers) who participated in the study. They were all extremely cooperative and very willing to spend a considerable amount of time helping me collect and validate the information presented in this document.

Infectious hematopoietic necrosis virus (IHNV) is a serious enzootic pathogen that infects several species of salmonids in western North America and is the causative agent for the disease, infectious hematopoietic necrosis (IHN).

We do not know what factors led to the 1992 and 2001 IHN epizootics in farmed Atlantic salmon. One hypothesis is that a certain group of returning wild salmon had higher IHNV prevalences and titres than usual and, consequently, were shedding more virus particles. Another hypothesis is that the first group of Atlantic salmon to become infected were stressed and therefore more susceptible to the infection. A third hypothesis is that even small variations in genetic sequences of the virus affect the virulence of the virus in Atlantic salmon and there is one or more stock of wild salmon, which are carriers for this more virulent variants. As a result of the cyclical nature of the sockeye life history, this variant would only appear every four to five years with the return of this stock.

A large study conducted by Meyers et al (2003), examined IHNV data collected by the Alaskan sockeye culture program between 1981 and 2000. They found that the prevalence of IHNV in the adult sockeye salmon fluctuates from year to year. Generally, the prevalence of infected salmon and the percentage of those infected with high IHNV titres peak and decline together. Interestingly, in 1992, the same year the first IHNV epizootic started in farmed Atlantic salmon in BC, the IHNV prevalence and the percentage of spawning Alaskan sockeye salmon with high viral titres were both some of the highest recorded levels–56.2% and 65.7% respectively. Unfortunately there has been no comparable work done on adult sockeye salmon returning to British Columbia rivers.

Horizontal transmission of the IHN virus occurs readily in both saltwater and freshwater (Traxler et al. 1998).

Different salmonid species appear to be sensitive to different genetic isotypes. For example sockeye salmon, Oncorhynchus nerka, are susceptible to the northwest coast IHNV isolates while chinook salmon, Oncorhynchus tshawytscha, are more susceptible to the Californian isolates. Rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss, are susceptible to the Idaho isolate.

Most of the losses associated with IHN, in sockeye salmon, occur in the freshwater alevin and swim-up stages. Disease in the seawater sockeye stages has not been as commonly observed, however, the northwest isolates are quite homogeneous indicating that continual mixing of the isolates has occurred over the generations. The only location where this appears possible would be in the ocean (Williams and Amend 1976, Traxler and Rankin 1989, Emmenegger et al. 2000). One such place could be the “Alaskan gyre”, the common feeding grounds for all sockeye populations north of Oregon (Emmenegger et al. 2000, Emmenegger and Kurath 2002).

Lab transmission studies have found that Atlantic salmon are very susceptible to IHNV infections (Traxler et al 1993). In 1992, IHN was diagnosed in a population of farmed Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar, in British Columbia (BC). Over the next four years, the disease spread to 13 separate farm sites within a 20 km radius of the index case (St-Hilaire 2000, St-Hilaire et al.2001). In the summer of 2001, nine years after the first epizootic, IHN was again diagnosed in a population of farmed Atlantic salmon. As in the

1992 epizootic, mortality as a result of the disease has been significant.

The British Columbia Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Farms (BCMAFF) and the British Columbia Salmon Farmers Association (BCSFA) commissioned the following report with the objective to: describe the 2001-2003 epizootic, outline possible risk factors and to provide suggestions on how to minimize risks (including research needs).

All companies with affected sites were interviewed. These companies were asked questions regarding their husbandry and management practices as well as specific fish history questions for each affected site. Similar questions, although not as detailed, were also asked about sites that remained IHN negative during the epizootic.

Companies that did not have any IHN infected sites were not interviewed. The risk factors discussed in the report were based on questionnaire findings as well as the current knowledge of IHN in BC.

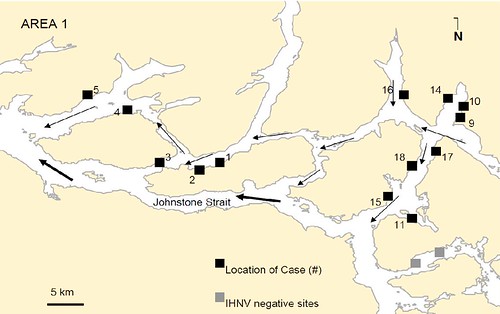

Between the August 2001 and June 2003, 36 Atlantic salmon farms developed IHN. Infections were identified in five separate areas; with the largest number of cases occurring in areas 1 (13 cases) and 5 (10 cases) (figure 1). All 14 Atlantic salmon farms diagnosed with IHN during the 1992 –1996 epizootic were located in area 1.

The first case, the index case, was diagnosed in late August 2001. The index case in the 1992 outbreak occurred in the same area and during the same time of year (summer) as this recent outbreak, perhaps indicating that the source of the viral exposure may be similar for both outbreaks.

Kurath compared the isolates of the 2001-2003 epizootic (sequence A and B) with those of the 1992-1996 epizootic and found that they are different. This data suggests that the two isolates from the 2001-2003 outbreaks represent two independent new introductions of IHNV into farmed Atlantic salmon with both local sources being enzootic to BC: one source originating on the east coast and one on the west coast of Vancouver Island (Kurath unpublished data).

Detailed mortality data was examined from 20 infected sites. The shortest time from apparent exposure to the virus to clinical disease appears to be seven days. This was observed in a group of smolts shortly after being entered into seawater. Figure 2 shows a representative mortality curve associated with an on-farm IHN outbreak. The curve shows a steep increase in mortality shortly after diagnosis of IHN on the site, with mortality rates spiking six to eight weeks into the epizootic. The epizootic on the farm appears to last 20 to 22 weeks. A study examining the 1992 -1996 IHN epizootic found a second mortality spike 30 weeks after the first (St-Hilaire 2000), this was not seen in any of the cases in this recent epizootic.

The shape of the mortality curve indicates most likely a common point source for the infection (i.e. high number of viral particles) (Baldock 2000). The rapid increase in the mortality as seen by the steepness of the curve illustrates the highly contagious nature of IHNV in an Atlantic salmon population.

Harvesting of confirmed positive populations were conducted according to the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) protocols with the exception of two cases where harvesting was completed (case 17, 18) before laboratory confirmation of IHNV was received.

Even though IHN is not a reportable disease, all companies kept the provincial and federal government agencies informed of positive results.

A/ Wild sockeye salmon

There is some evidence that wild salmon could have been the source of the infection for the initial few cases. For example, the first three sites to be diagnosed with IHN were all located in the same channel. Infection was detected in late August 2002, at which time there were a large number of returning sockeye, chinook and coho salmon in the channel. IHN is a common disease of sockeye salmon known to cause high mortality in early life stages (Williams and Amend 1976, Traxler and Rankin 1989). Ribonuclease protection assay (RPA) work found that the IHN virus isolates from the farmed salmon are similar to those found in local sockeye salmon (Emmenegger et al. 2000, Emmenegger and Kurath 2002, Kurath unpublished data).

Normally, sockeye return from the common feeding grounds off Alaska to freshwater as four or five year olds (Emmenegger et al. 2000, Groot 1996). The sockeye populations that would potentially pass through Area 1 to spawn would include many of the Fraser River runs, as well as many minor runs that enter the local rivers and lakes, such as the Philips Arm, Bute Inlet and Heyden River runs. Figure 9 shows the sizes of the Fraser River runs from 1990 to 2001 (from the Pacific Salmon Commission). In 1992 and 2001, the total production for the Fraser River runs was 6.4 and 7.2 million respectively. This is considered a moderately low return. Low runs can be cyclical, or may be related to some external environmental factors such as water temperature, lack of food or even disease. There is very little data available on the non-Fraser stocks

We do not know what factors led to the 1992 and 2001 IHN epizootics in farmed Atlantic salmon. One hypothesis is that a certain group of returning wild salmon had higher IHNV prevalences and titres than usual and, consequently, were shedding more virus particles. Another hypothesis is that the first group of Atlantic salmon to become infected were stressed and therefore more susceptible to the infection. A third hypothesis is that even small variations in genetic sequences of the virus affect the virulence of the virus in Atlantic salmon and there is one or more stock of wild salmon, which are carriers for this more virulent variants. As a result of the cyclical nature of the sockeye life history, this variant would only appear every four to five years with the return of this stock.

A large study conducted by Meyers et al (2003), examined IHNV data collected by the Alaskan sockeye culture program between 1981 and 2000. They found that the prevalence of IHNV in the adult sockeye salmon fluctuates from year to year. Generally, the prevalence of infected salmon and the percentage of those infected with high IHNV titres peak and decline together. Interestingly, in 1992, the same year the first IHNV epizootic started in farmed Atlantic salmon in BC, the IHNV prevalence and the percentage of spawning Alaskan sockeye salmon with high viral titres were both some of the highest recorded levels–56.2% and 65.7% respectively. Unfortunately there has been no comparable work done on adult sockeye salmon returning to British Columbia rivers.

Research has shown that Atlantic salmon can become infected when placed in close proximity to an infected salmon (Traxler et al 1993). However, the minimal dose and exposure length required for transmission is not known.

How can this risk be minimized?

At this time, knowledge is insufficient to be able to establish protocols that would, in effect, eliminate this risk. Therefore, research in this area is critical. There should be a concentrated effort to support disease research in wild fish.

The presence of an IHN positive population, undergoing an epizootic, could provide a continuous reservoir of virus not only for the infected site itself but also to the surrounding area (i.e. downstream). All of this is merely a hypothesis, however, and further research is required.

There is an added level of concern with the protocol, when it was noted by some during the interview, that the addition of salt water artificially increased the detectable level of chlorine. Finally, there was some difficulty ensuring complete mixing of the chlorine and wastewater. The question arises as to how effective the protocol is in destroying the virus in large volumes of water, especially when complete mixing is difficult and organic levels are high. It is possible that there may have been some unintentional releases of IHNV infected water.

As stated earlier, most plants that process farmed salmon in BC have set up treatment facilities to successfully disinfect harvest by-products. However it has to be remembered that IHN is also a common disease in wild salmonids in BC such as sockeye and the majority of the processing plants that handle wild fish still do not treat their process water prior to discharge. These facilities could pose a substantial risk to the farmed fish population. Yea, there is NO PROBLEM there!

Many of the management changes would only occur after laboratory confirmation of IHNV, since the associated costs would be significant. Consequently, delays in diagnosis increase the prospect of not tightening the biosecurity barriers quickly enough.